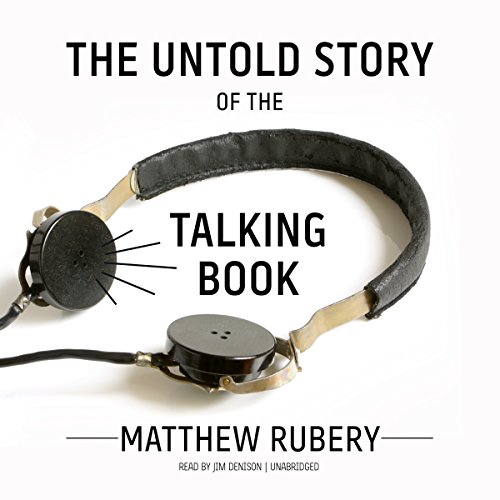

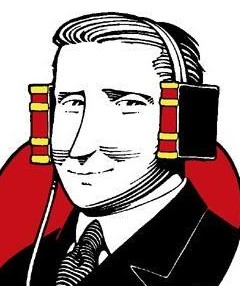

My research into the origins of the audiobook industry has led me to interview a few of its pioneers. Last week I spoke with Henry Trentman, who founded Recorded Books Inc in 1978. Its tapes were targeted at the growing number of commuters clogging up America’s highways. Few bookstores stocked audiobooks until the mid-1980s, but bored drivers could rent them through the mail for roughly the same price as a hardcover book. The company launched the careers of many beloved narrators including Frank Muller; one of my personal favorites is his recording of Motherless Brooklyn, a detective novel featuring a narrator with Tourette syndrome. You can hear a sample here. Recorded Books is still in operation today and, as of January 2014, had over 13,500 titles in its catalog.

MATTHEW RUBERY [MR]: How did you come up with the idea to start Recorded Books?

HENRY TRENTMAN [HR]: I did not come up with the idea. I copied it from Duvall Hecht’s Books On Tape. He was the clever guy who thought of recording unabridged titles and renting them through the mail, and that was one of several keys to the growth of the industry.

Here is how I got into it: although I did not realize it at the time, my three years in the Marine Corps had several major impacts on my life, one of which was the realization that I wanted to be my own boss. I really did not like people telling me what and how to operate. By the late seventies I was an independent manufacturers’ rep selling semiconductor and high vacuum equipment from Delaware to Eastern Tennessee. It wasn’t unusual to travel 3 or 4 hours between customers. That’s a lot of time in the car, and the radio stations down here, you kept losing them, and I’m not a big country & western or rock & roll kind of guy; I was more into classical and folk music and old time country, none of which were easy to find. I was just bored.

I started going into the libraries and taping the Caedmon records onto my little cassette player, which sat on the seat next to me. I copied every Caedmon record in the Arlington Public Library on to my cassette recorder. They were consumed on one trip to Knoxville, Tennessee. The problem was there weren’t too many records, and records aren’t very long anyway. I had to ration them on my longer trips and not use them on the shorter ones. The one I remember the most was this one about Dylan Thomas, and Alec Guinness was the actor in it. He read Dylan’s poetry much better than Dylan did—because he was an actor. That was a very enjoyable experience, so I tried to reproduce that with other records but couldn’t find any. Sunday night one of the local public radio stations had an old time radio show hour, and I copied all their material. Taping old radio shows was okay, but it was time-consuming to do it, and really old radio shows aren’t that interesting once you get over the quaintness of them.

Then one day I opened my American Express bill. It had a little article about one of their clients, Books on Tape out in California, which rented unabridged books through the mail, and I said, “Gee, that’s absolutely great, that’s exactly what I like,” because I’ve always been a heavy reader. I ordered one, listened to Wolfram Kandinsky read a spy novel, and I was hooked. After listening to a couple, I decided that there was room for another company and maybe this would be a way to get out of the rep business, which I did not particularly like, and into making my own product. To give you an idea how naive I was about it, I looked upon it as a manufacturing business not publishing. So I decided to try to do it on the East Coast and it took about a year, year and a half, to set it up and arrange it, get the rights to a couple of books. It was an interesting start-up.

MR: How did you view Books On Tape—as a competitor or something else?

HT: Well, I’m a salesman, and everyone who has a similar product is a competitor. But I never really worried—at least I tried not to worry about my competition. If you try to make what your customers want, the competition has to worry about you rather than you worrying about them. I mean, in theory. I can remember listening to an abridged book about Ray Kroc, the guy who founded McDonald’s. They asked him if he had a competitor drowning in the swimming pool, what would he do? He said, “Well, I’d take a garden hose and stuff it down his mouth and turn it on.” And then in the same breath he said he’d never worried about his competitors; he was so busy growing his own business, he didn’t care what they did, he just wanted to do what he thought was the right thing to do. So he never reacted to his competitors, and I think I was pretty much the same way. I mean, I heard that book years after I’d started the business and thought of it as a confirmation of how I acted. I thought it was a big world. I was on the East Coast so I had a local postage advantage. And I didn’t really talk to Dewey [Duvall Hecht] for a number of years after we started up. I met him at a couple of trade shows; he was a very nice guy, and I think we were friendly competitors. I’m sure he would have loved it if I went out of business, and I would have loved it if he’d gone out of business.

MR: It sounds like you had no literary background or publishing background?

HT: No, none whatsoever. I guess I’m a mild dyslexic in that I can’t spell very well, read very slowly, and my writing is horrible. So I was an absolutely atrocious English student. I’d always enjoyed reading, but most literature classes either didn’t pick particularly interesting books or they’d analyze them to death, which is not what writing is all about, in my mind. I had the worst background in the world for what I did.

MR: How did you choose the name Recorded Books?

HT: Well, you know, it was really funny, if I had it to do over again I would definitely not name it Recorded Books. My mentor in business, Pete Fletcher, had once mentioned to me—and I remembered it, this was way before Recorded Books—that you should always try to name your company after the product that it makes. That seemed to make sense, so that’s what I tried to do. Books on Tape had the first shot at it, and they picked the best of them all, “Books On Tape,” except, of course, it limited it to tape, so if the media ever changed—which, back in the days of cassettes, really wasn’t a thought—you had a problem. And so I looked for something a little more generic. I think it was a young woman who was working part-time for me who came up with the actual name. If I had it to do over again, I would have chosen another name.

Here’s why it was a bad idea and here’s why I would not do it again. And I did not repeat this blunder when we started our English operation. I named it after a person, my great-great-grandfather. The reason I did that is people were constantly referring to one company and the other by the same name, or the product by “Do you listen to books on tape?” or, later, it was “Do you listen to recorded books?” We were constantly getting credit for [Books on Tapes’] stuff, and I’m sure it was vice-versa. It was because the names were so generic, it became like Kleenex—it became the name of the product even though Kleenex wasn’t making the tissue. If I had to do it again, I probably would have picked someone’s name, a human name, and then when you referred to that company, you wouldn’t refer to it as books on tape or recorded books, meaning the other company.

MR: The first book your company recorded was Jack London’s The Sea-Wolf. Do you remember why you chose this title to start with?

HT: I remember we wanted to get going and we didn’t have rights to anything else yet. So the first book had to be in the public domain. Jack London was a dramatic, still modern writer. I had always liked the story of London’s The Sea-Wolf, and we had found this actor, Frank Muller, who just—who just brought that book alive. You forgot you were being read to. You know you have a good reader when, after the first three or four minutes, you’re no longer conscious of him reading to you. Then you’ve got the guy. As long as you’re conscious of the reader, it gets in the way of the story.

MR: It seems like unbelievable luck to have started out with such a world-class narrator—how did you find him?

HT: I had a friend who was in dinner theater and went around to Arena Stage and a couple of other places and put ads on the bulletin boards in the back rooms there for actors. Arena Stage was the premier stage in Washington, DC. It was Frank’s girlfriend at the time, Kitty, who forced him to come to audition. Frank was a little hesitant, which was surprising; he’s not a shy guy but he is a procrastinator. He was just hesitant to come out; he was young, probably thirty at the time. So she got him to come out. He was just great, he really was. He had the goods right from the beginning.

MR: Your company’s known for unabridged books. Why did you decide not to do abridgments?

HT: An abridged version—unless it’s a horrible book—is never as good as the original. If the writer knew what he was doing, he’d already taken all the fluff out of it. So, really, you’re taking all the meat and just ending up with the skeleton when you’re doing abridged. And remember, I was looking for time in the car, so I wasn’t trying to save time, I wasn’t trying to get a book done in two hours; I would have loved it if it was fourteen hours because I was spending a ton of time in the car. The major publishers were concerned about time because they had to sell these things and to sell two tapes for 14 bucks was a lot easier than selling fourteen tapes for $100. It wasn’t a book store item. And the major publishers—the thought of rental was just absolutely beyond their ken. The conventional publishing world was so different from the way I thought. I just couldn’t believe these guys. I thought, they came from a different world than I did. The abridged book had zero interest. I just couldn’t imagine anyone willingly listening to an abridgment if they could listen to the unabridged. And, since you normally don’t keep books—you know, you read them once—for 14 bucks, you’d get a one-time listen or a thirty-day listen to the unabridged, or you could get the abridged and be done with it in two hours but you got to keep it.

MR: Did you have any guidelines about how narrators should read your books?

HT: You really cannot train someone to read a book. They either have it or they don’t. We found actors who read the way we wanted them to—I think that’s basically the answer to your question. I wanted someone to bring the book alive. Usually, if it was fiction, being able to give each character the personality that fit the personality the author was trying to develop was pretty key. But you couldn’t ham it up, you couldn’t overdo it. It was really a drawing back. And someone like Frank [Muller] could do it; he was just a natural. Barbara Rosenblat, she could do it. Flo Gibson almost hammed it up, but she got away with it; she was good for certain types of books. So we would cast our books; Frank could not read every kind of fiction, and he actually wasn’t very good at non-fiction.

And the people reading non-fiction—it’s hard to describe—but when you heard it, you knew this is how I want to listen to The Distant Mirror by Barbara Tuchman, which was like a total of 28 cassettes—I mean it was a long book. The person who read it, in that case, had to have a really good grasp of German and French and Italian, a little bit of Turkish; because when you try to fake the pronunciation of the word, you know it’s a fake. Even though you haven’t a clue how it’s supposed to be pronounced, you knew that wasn’t it. We researched the books when we did them, and we tried to get the dialects correct if there was a dialect involved, and we certainly tried to get the pronunciation correct. Fortunately we were in New York, and we had these guys who worked part time for us who would work in the studio with the actors. We always had one person monitoring it, you know, handling the tape deck, but his real job was to make sure the book was read properly. A lot of guys who are trying to break into the world of acting tend to be on the intellectual side anyway, so they really got into it. We had this huge talent pool of people working behind the scenes who helped us get it right, and helped the actor get it right.

MR: How did you cast narrators for books?

HT: Each book was a separate thing. Of course, once someone started reading a series of books, we tried to keep them in the series. It was a collaboration, I guess, sort of. Claudia [Howard], who ran the studio, would go out and was continually auditioning people. Then she would get together a bunch of tapes of various people for, say, a book that we had. If we already knew the person, it was easy; we knew the book, and we’d say, “Oh yeah, Frank could read that, that’d be perfect for him.” Or: “This is a George Guidall book.” But, if we were looking for new talent—which we constantly were, because it was so hard to find people who could read, even in New York, which is where all the stage actors were, and a lot of commercial voice work—it was just really hard. Claudia was constantly holding auditions, and she would get together a bunch of them, and she’d send one set to Sandy [Spencer], my partner, and then she’d send one set to me, and we’d go through and grade them. We never agreed, but eventually we got to where we wanted to. Usually when you had someone that was really good, everyone agreed. It’s when you had someone that was less talented, where you’d have one person say “Aw, this person’s okay,” and someone else would say, “No, they suck.” That’s how you would do it. I mean, you knew it when you knew it.

MR: Do you see any difference between listening to a book read aloud and reading it in print—are they the same thing in your eyes or something different?

HT: It’s funny. I don’t listen to books much anymore, because I don’t travel a lot; when I travel, I still like to listen to them. Even though I’m a very slow reader, I prefer reading the printed page because, for one thing, it’s more private, and you develop your own characters. I mean Frank [Muller] would always develop the characters better than I ever would in my imagination; he just had that knack. I just prefer reading them by myself. Whereas my wife, who reads like a million miles an hour, she prefers to listen to books. I think it’s a personal preference.

MR: Did you ever encounter any hostility or skepticism toward your books?

HT: Hostility is probably too strong a word, but yes. Some people could be very small-minded. There is nothing superior to getting it from the printed page than it is from hearing it read out loud. And the better the literature, the better it sounds read out loud. I never could understand why people thought there was something magical about reading it with your eyes. I mean, there was a lot of snootiness about “My imagination’s better than the other guy’s.” You can actually read a book and then listen to it and just get a different experience, because you’ll get a different interpretation. But, you know, two interpretations can both be good. You just have to be not so possessive of your own.

[This interview is reprinted with the permission of Henry Trentman. The phone interview took place on October 16, 2014. Copyright © Matthew Rubery 2014.]