Good news for audiophiles: one of the oldest—maybe the oldest—set of talking book recordings made in Britain has been found.

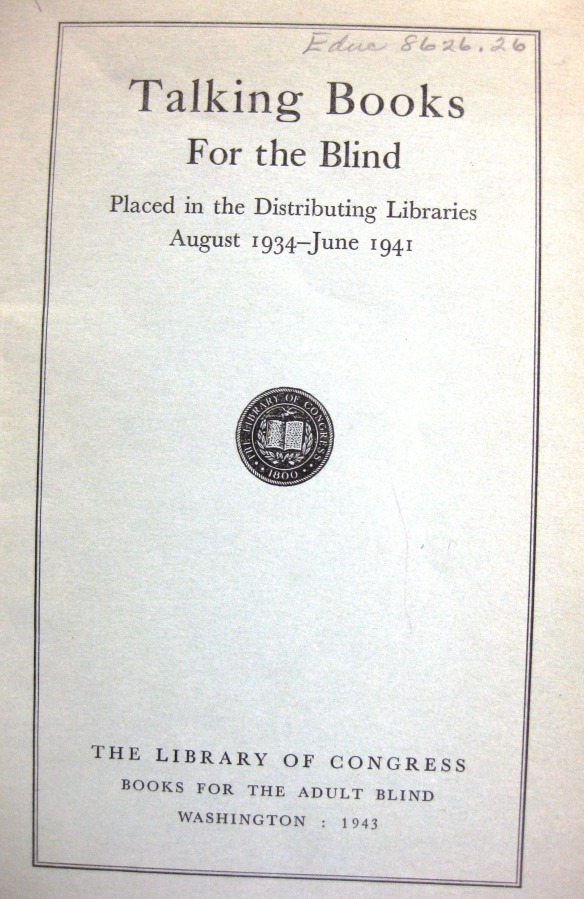

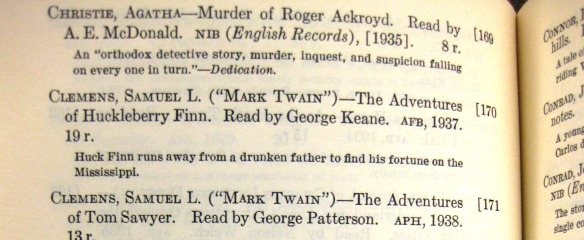

I’ve spent the past few years searching for the first records made by the Royal National Institute of Blind People’s Talking Book Library in 1935. The first titles to be recorded were Joseph Conrad’s Typhoon, Agatha Christie’s The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, and the Bible (The Gospel According to St. John). They were made on 12-inch discs that played at a rate of 24 revolutions per minute (RPM), much slower than the standard rate of 78 rpm used for music records at the time (long-playing records would not reach the commercial market until 1948). This enabled the RNIB to fit an average-sized novel onto about 10 discs. These records are among the world’s first audiobooks (a term that didn’t come into use until the 1990s) as well as a valuable part of the nation’s cultural heritage.

Unfortunately, most of the earliest talking book records have been lost or destroyed. I’ve never been able to find any surviving copies of the first five titles made for the Talking Book Library (the other two were Axel Munthe’s The Story of San Michele and William Gore’s There’s Death in the Churchyard). Talking book records were made of shellac and therefore fragile; I can’t tell you how many times I’ve come across shattered pieces of a disc. Heartbreaking!

The RNIB donated all of its historic recordings to the British Library’s Sound Archive a number of years ago for safekeeping. When I began writing my history of audiobooks, however, I was surprised at how few of the initial titles remained. For example, none of the recordings made during the Talking Book Library’s first year could be found on the shelves. The RNIB’s website featured an early recording of The Murder of Roger Ackroyd that turned out to have been made at least a decade later (many of the initial titles were re-recorded to improve quality since sound technology had improved dramatically by then). What happened to all of the early recordings?

I would spend the next few years poking around archives, corresponding with librarians, speaking to blind patrons, phoning vintage record collectors, and pursuing various other leads in search of the missing records. There were minor victories: the RNIB’s dedicated librarians found a copy of Elizabeth Gaskell’s Cranford that was made in 1936, a year after the library opened. We were getting closer. Then, with the invaluable assistance of the British Library’s sound curators, I was able to figure out where the records were manufactured.

The titles had been recorded at a studio in Regent’s Park. But, in order to reduce costs, the studio then sent off the master discs to be pressed by major record labels like Decca and HMV. This led me to the EMI Group Archive Trust in Hayes, Middlesex (one of the most fascinating heritage collections I’ve ever encountered, incidentally), whose staff were able to locate a single disc from the set containing William Makepeace Thackeray’s The History of Henry Esmond—by my reckoning, the sixth title to be recorded in Britain. Closer still!

It was reassuring to know that at least two of Britain’s initial batch of talking book records still existed—or at least parts of them. But there was still no sign of the other records. No one I spoke to or corresponded with knew anything about them. My advertisements in places like the City of London Phonograph and Gramophone Society newsletter and Association for Recorded Sound Collections email discussion list went unanswered. I’d all but given up hope.

Then came the lucky break. Since 2013, I’d been corresponding with a vintage record collector in Canada named Mike Dicecco about his unique collection of discs that play at unusual speeds. I got in touch with him after coming across his fascinating account of 16 rpm records in the Antique Phonograph News. These records were commercially available for a brief period around the 1950s and feature in my history of audiobooks. But I didn’t realize that Mike also had 24 rpm records made for blind people. After reading a journal article I’d written about the history of Britain’s Talking Book Library, he sent me a list of the titles in his collection. I nearly jumped out of my socks when I saw Conrad’s name!

It’s extremely likely that Conrad’s Typhoon was the first talking book made in Britain. It’s widely believed that the first one was Agatha Christie’s The Murder of Roger Ackroyd but, as I note in my book, I’ve never been able to confirm with certainty whether the first recording was Conrad or Christie. What I do know is that Anthony McDonald narrated the first talking book ever made (Blind Veterans UK’s Captain Ian Fraser, who oversaw the initial recording sessions, states this unequivocally). The fact that McDonald narrates the Conrad records makes me suspect that this is Britain’s first talking book; the Conrad material (the last disc contains an excerpt from the memoir The Mirror of the Sea) was also thought to be out of copyright, which was an important factor in choosing the initial lineup. It’s possible that McDonald also narrated the Christie records (we don’t know who did), in which case the mystery will remain unsolved. But, for now, Conrad’s the frontrunner.

Either way, I’m thrilled we’ve been able to preserve at least one of the first two talking books made in Britain. Mike has generously agreed to provide the British Library with a full recording in order to ensure that the album is not lost to posterity (again).

You can hear a short clip from Typhoon played on BBC Radio 4’s “World at One” (starting at 44.00).

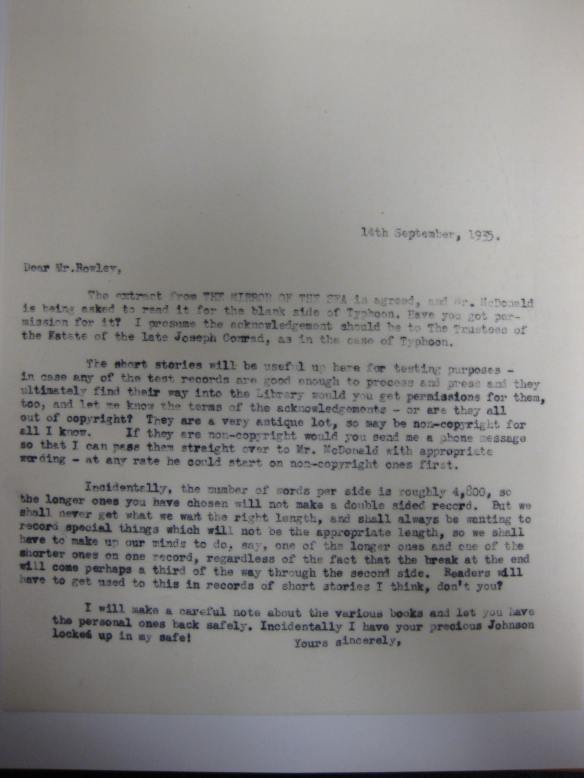

You can also read a letter written by Fraser about the recording:

The album’s discovery in Canada makes the story all the more intriguing. How did it get there? My search was limited to the UK and US as the most obvious destinations. It seemed unlikely to me that fragile shellac records that couldn’t survive in the UK would be able to withstand the strains of a transatlantic journey. My best guess is that a veteran carried the records back to Canada with him. As I explain in my book, the RNIB’s Talking Book Library had been started for blinded soldiers of the First World War, and the technology was eventually shared with Commonwealth countries such as Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and India. What I love best about this story: Conrad’s Typhoon tells the story of a ship’s safe passage through a perilous storm. How fitting that the records themselves survived the long voyage.

The remarkable find of Conrad’s Typhoon after all these years now gives me hope that other recordings will turn up too. If anyone comes across an old record in their attic, especially one with braille on the label, then please contact me immediately!

You can read news coverage of the discovery here:

“Unique copy of first full-length audio book found in Canada” (Guardian)

“World’s first audiobook tells its tale again” (The Times)

“Long-lost audiobook – one of the earliest ever published – discovered in Canada” (Los Angeles Times)

You can hear me talk about the recording here:

“Hear what may be the first full-length audio book, found in Canada” (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation)