More good news: another one of the first talking books recorded in Britain has turned up! As I wrote in my last post, I’ve spent the past few years trying to find surviving copies of the earliest books recorded by the Royal National Institute of Blind People for the Talking Book Library in 1935. The first three were Joseph Conrad’s Typhoon, Agatha Christie’s The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, and The Gospel According to St. John. A record collector in Canada contacted me a few weeks ago to let me know that he owned all four discs of the Conrad album. And now, in response to that re-discovery’s press coverage, a British collector informs me that he has The Gospel According to St. John. It’s a miracle!

Adrian Hindle-Briscall emailed me after reading about the Conrad discs in The Times to let me know that he owns the first of three discs in the St. John set. Apparently he bought the record many decades ago at the old Gramophone Exchange in Wardour Street. You can listen to a recording of the disc on Hindle-Briscall’s website: http://www.aeolian.org.uk/rnib/

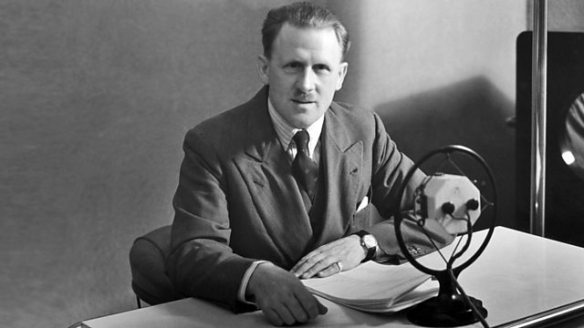

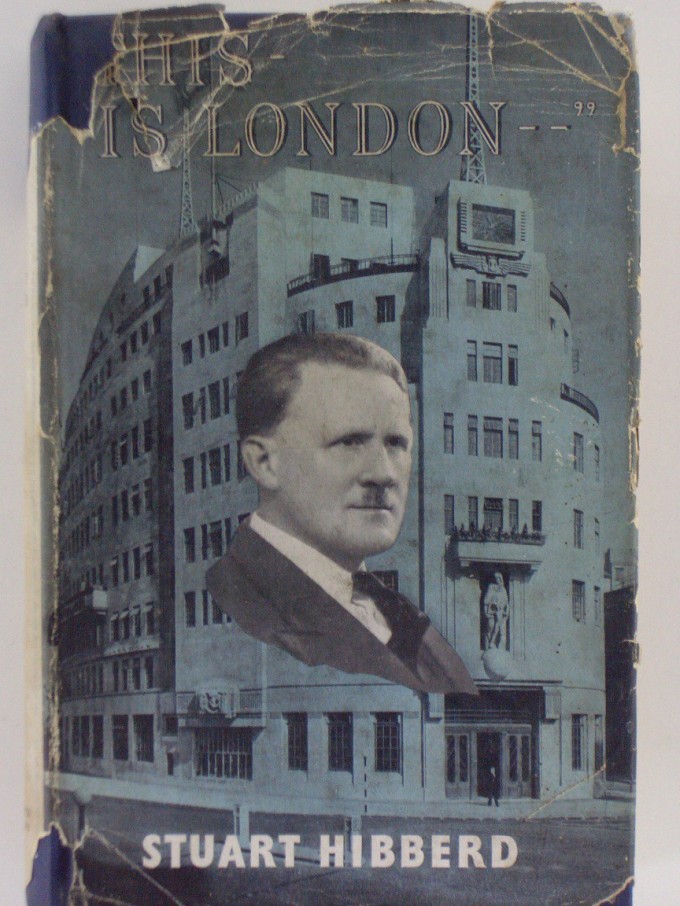

The narrator is Stuart Hibberd, one of the first professional announcers at the BBC, where he read the news and presented cultural events. His received pronunciation was typical of announcers at the time. In “This—Is London…” (1950), a diary covering 25 years (1924-1949) of working for the BBC as its Chief Announcer, Hibberd recalls meeting with Ian Fraser, the Chairman of Blind Veterans UK (then St. Dunstan’s) and a key figure in establishing the Talking Book Library, to discuss recording the Bible:

“1935: On 31st October I went to have tea at St. Dunstan’s with Sir Ian and Lady Fraser to discuss the Talking Book, recordings of speech reproduced on slow-running discs, continuing for half an hour before any change of record is necessary, an invaluable aid for blind people, and an invention which has since proved very useful to us from a recording point of view.” (119-120)

Fraser told Hibberd that he wanted experienced broadcasting voices to narrate the talking books and asked him to read portions of the New Testament. It was a good choice: Hibberd was not only an experienced speaker but had also thought a great deal about adapting printed narratives into sound, as he explains:

“The problem of writing for the voice and thinking in terms of the spoken word, as distinct from the printed page, has been with us almost since broadcasting began in this country. It was soon realised that a special technique would have to be developed, as what was required was shorter sentences than when writing for the eye and the use of as much colloquial English as possible. This was made clear when some well-known scenes from Dickens were broadcast in 1924.” (301)

The Bible is the most popular talking book ever recorded (the Book of Talking Books, as I like to say). The Gospel of John was particularly relevant for its scene of Jesus healing a blind man and thereby turning darkness into light. The British & Foreign Bible Society paid to have this section of the Bible recorded before any others because of its ties to the Venerable Bede, whose 1200th anniversary took place the same year as the opening of the Talking Book Library. The Society went on to pay for the other Gospels to be recorded by Hibberd too.

Let’s hope more such finds are to come. Dare I hope that the Agatha Christie records will turn up one day?